Meeting Energy Demands While Facing the Challenges of Electric Grid Instability

Exploring clean, viable, and available options for electric independence

Sponsored by PROPANE Energy for Everyone

Joost Moolhuijzen

Renzo Piano Building Workshop

Sponsored by Vitro Architectural Glass

Sonic Shangri-la – The Art of Sound

Exploring the Harmony of Innovation, Design, and Acoustic Excellence

Sponsored by Armstrong World Industries

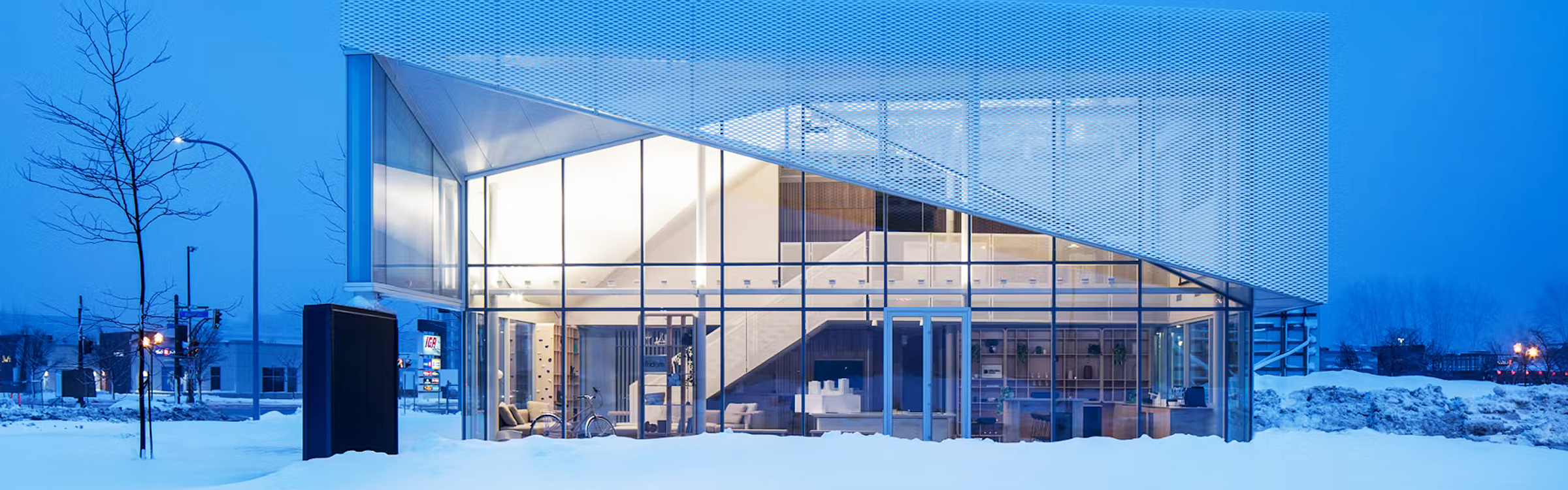

Expanded Metal and Perforated Mesh Interior and Exterior Applications

Starting a Design and Understanding Material Features & Benefits

Sponsored by AMICO Architectural Metal Systems

.jpg)