Sonic Shangri-la – The Art of Sound

Exploring the Harmony of Innovation, Design, and Acoustic Excellence

Sponsored by Armstrong World Industries

Next-Gen Leadership

Essential Training for Architecture Firm Growth

Sponsored by BQE Software

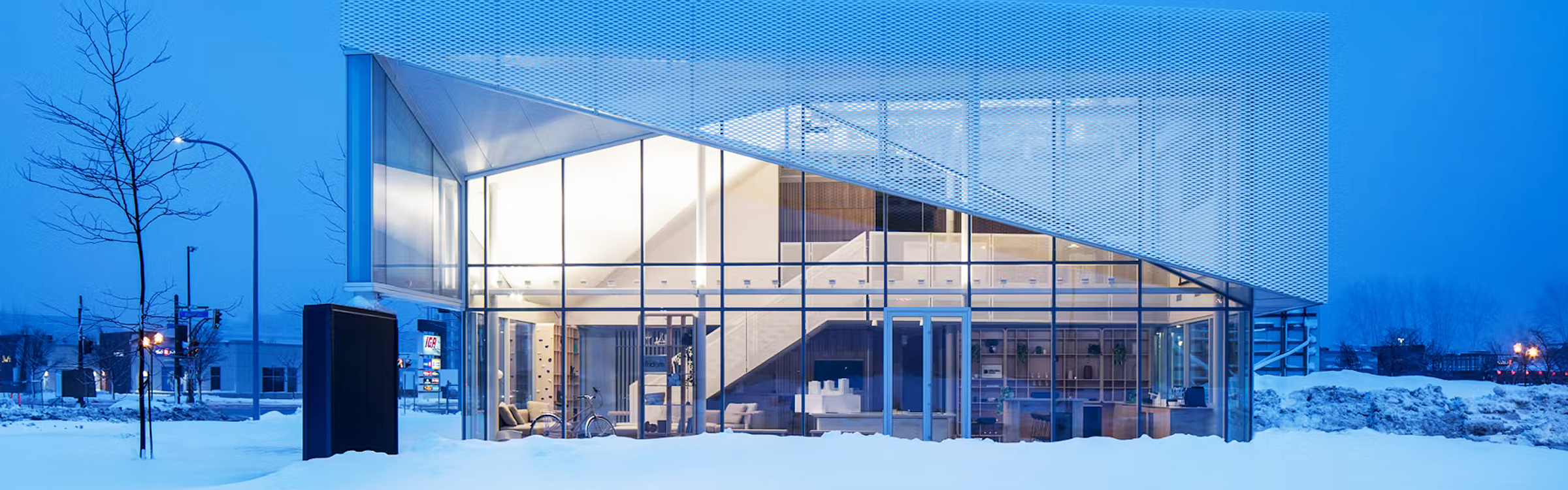

Expanded Metal and Perforated Mesh Interior and Exterior Applications

Starting a Design and Understanding Material Features & Benefits

Sponsored by AMICO Architectural Metal Systems

Built to Protect

Durable Wall Protection for Durable Buildings

Sponsored by Inpro

.jpg)